Exhibition SALT 2019/20

Violeta Čapovska-Exhibition SALT 2019/20

Museum of City of Skopje-Macedonia

SALT, Open Graphic Studio, Museum of City of Skopje, Macedonia

December 2018/January 2020

Salt, 2019/20, Open Graphic Studio, Museum of City of Skopje, Macedonia

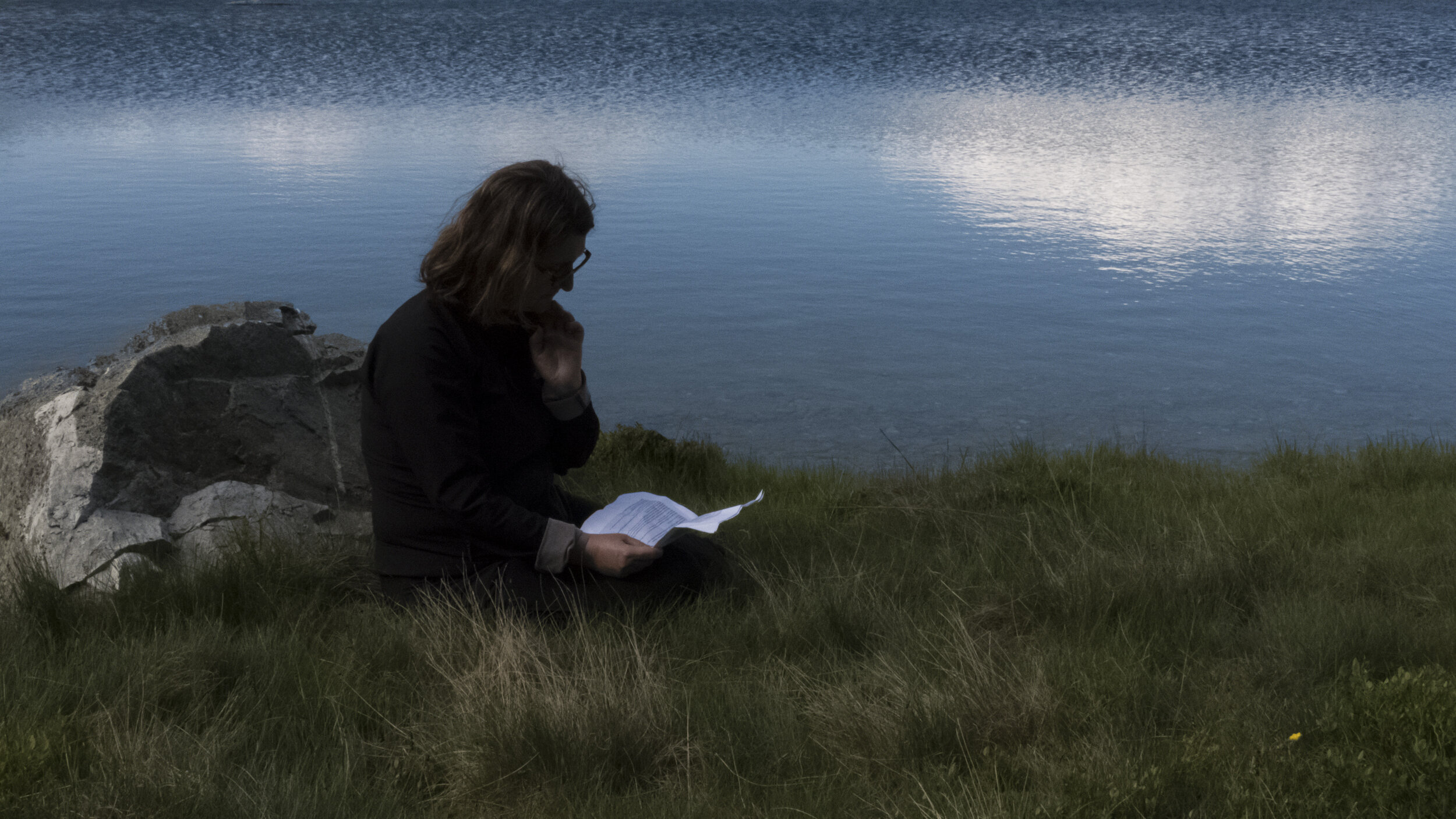

Photo: Stanko Nedelkovski

Installation view, Salt 2019/20

salt

Photo: Stanko Nedelkovski

Installation view, Salt, 2019/20

salt, photographs

Photo: Stanko Nedelkovski

Dr. Suzana Milevska

In July 2018 Violeta Čapovska completed her land-art performance Salt. This was the third part of Čapovska’s long-term project that formed a kind of trilogy - it followed her previous land-print projects: Small Lake (1994) and I and the Eye (1996). What is common for all three projects and also makes them specific is their unique location: they all took place at the Small Lake on Baba Mountain in Macedonia. However by climbing the mountain once again all the way to the Small Lake while realising the latest project Salt Čapovska managed to address the various aspects of the relationship between her cultural and gender identity, nature, and her artistic practice.

Despite the many resemblances between Salt and the two previous iterations of her long-term project, such were the climbing, walking, and other “small performative acts” that the artist performed in order to delineate her complex relation with this particular lake, the latest project focused on entirely new elements and metaphoric repositories. For example the previous projects included mainly reflective objects (champagne glass, magnifying glass, or mirror) that established the reflexive, meditative, and mnemonic relation that the artist was continuously establishing with the location and its surrounding nature: the lake’s water and the mountain’s soil.

The Small Lake, particularly its purity and the incommensurable sublimity of nature in general could be interpreted as metaphors for temporality “culturalscapes” and “memoryscapes.” During the three projects particularly for Čapovska was important to stress the impossibility to represent the sublime and the difficulty of preservation of the fading childhood’s memories to aesthetical and ethical purity from the past. Thus in parallel to the objects that the artist borrowed from her grandmother’s house the projects included different print-making materials and graphic processes in line with Sigmund Freud’s concept “mystic writing pad” that stands as a metaphor for different layers of memories overwriting and erasing each other.

Here it is important to address the distinctive complex connotation of the material “salt” from the title of the latest project (and the exhibition) and to unravel the specific background and development of the entire concept. At first sight the art project’s concept and its structure are very simple: the artist aimed to climb once again to the Small Lake, to walk a circle around it and to “mark” her walk by a trace made of salt. She brought salt with her, but not any kind of salt. The origin of the salt was important in the artist’s words. The salt actually consisted of a mixture of different kinds of salt that originated from Europe and Australia as a kind of metaphor of the intersection and marriage between different cultural identities.

Čapovska’s ongoing concerns and the main focus of her projects is the possibility to return to the same. She admits that each time it is more difficult to climb the mountain and to make the full “circle” around the lake which circumference is (actually during the third project she didn’t even complete the tour).

There is no eternal return in terms of the old Nietzsche’s phantasm and myth of temporality. Nature changes, but its changes affect mostly our capability to co-exist and endure and live-through the changes that are effects of our actions. In Difference and Repetition Gilles Deleuze addressed in detail the Nietzschean problematic of the “eternal return of the same.” turn the technological means in a metaphorical device for pointing out the potentials and dangers of the return of the different, not the return of the same, in Deleuzean terms.

It is not the same which returns, it is not the similar which returns; rather, the Same is the returning of that which returns – in other words, of the Different; the similar is the returning of that which returns – in other words, of the Dissimilar.

Deleuze’s unorthodox emphasis on eternal recurrence as contaminated by inevitable difference leads to an entirely different understanding of temporality. According to his older pivotal book Nietzsche and Philosophy, first published in 1962, he already announced that it is not the empirically same, but difference, multiplicity and becoming which return. What remains eternal and ‘the same’ is the movement of recurring itself. “It is not the ‘same’ or the ‘one’ which comes back in the eternal return but return is itself the one which ought to belong to diversity and to that which differs.” For Deleuze eternal return implies that difference and becoming, as basic ontological principles, split the very heart of being from the beginning, and thus diversity and multiplicity cannot but fundamentally occur, which is recur.

Deleuze argued there are two aspects of the eternal return in Nietzsche. The first is its cosmological aspect, under which Nietzsche attacks the thermodynamic notion of entropy prevalent at the time of his writing. The second one is the ethical one, through which one selects the past that has to return to one’s present as if this present were perpetually repeated (e.g. the concrete and recognisable images from different historic events included from journalistic reports in the same work). Both aspects are important from today’s ecological perspective and for the project Salt.

Salt as durable substance (Sodium Chloride) that dissolves in water but doesn’t evaporate has additional pertinent significance. To be more precise in a case of imbalance of the salinity of the fresh and salt waters can subsequently cause imbalance and disruption of the micro and macro ecosystems and can affect biodiversity depending of the society’s capacity of managing the salinisation. The demarcation of the lake’s shape during the artist’s performance during which she was slowly walking around its shore as she was pouring small amounts of salt in irregular line was also a kind of ephemeral print that could be also interpreted as pointing the borderline between the intact nature and our questionable actions and calling for “paying attention” in Isabelle Stengers’ understanding of the term.

Since the early 1970s, many feminists, have defended the assumption that the environment is a feminist issue. Particularly important is the movement of ecological feminists ("ecofeminists"). For example Karen J. Warren was among the first leading ecofeminist theorists who recognised the importance of this relation and pointed to the urgency of looking at the similarities between the women's movement and the ecology (environmental) movement. In her introduction to Environmental Philosophy: From Animal Rights to Radical Ecology. Englewood Cliffs, she stated that “many feminists have argued that the goals of these two movements are mutually reinforcing; ultimately they involve the development of world views and practices that are not based on male-biased models of domination.” Similar arguments of the collaboration between ecological and feminist movement due to their common adversary - the male domination in various decisions regarding the political, systemic, structural, economical, and environmental issues - were developed by Mary Daly.

However, sometimes in art and writing about art projects that address environmental topics the ecological arguments are obscured and contradictory to the ones of the feminist critique and it gives way to possible conflation of the essentialisation of the relation between women and the environment and to some kind of simplification of the political connectedness of feminism, art and ecology. Although Čapovska’s project is not focused on discursive analysis of the major arguments of feminist and ecological theorists the project Salt (as well as the first two parts of the trilogy) makes clearer the argument that ecology and feminism can and should learn from each other, in many different ways. Obviously, the artist engaged with the complex relations between woman, nature, and art. Thus it is important to emphasise that Čapovska interpreted nature as culture, and not as a material resource that could be exploited endlessly in human interests.

For the artist the salt and lake offer the symbiotic context that enables our cultural anchoring in nature even when one decides or has had to leave the original territorial and cultural landscape. Thus with its subtlety and complexity the project Salt could also motivate us to look more carefully at the potential misunderstandings that could stem from the misleading essentialist ways in which some theoretical assertions of ecofeminism have been simplified, appropriated and recontextualised in contemporary art, in visual and popular culture, or throughout digital media and social networks. The danger of wrongfully representing the relation between women and nature in essentialised way when dealing with ecological and environmental issues in the project Salt is circumvented by the artist’s focus on the intersection between the nature and the cultural and gender identity.

Notes:

i It’s important to stress that this project took place twenty five years after Čapovska climbed to the Small Lake for the first time in order to realise and record her art project at this location. The project Salt thus also points the artist’s intimate relation to the nature and culture of her country of origin: Macedonia, although she lives and works in Melbourne, Australia.

ii Small Lake is one of the two lakes on Baba Mountain that is at elevation of 2180 m, near its peak Pelister.

iii In 2019 Violeta Čapovska presented the project Salt in the frame of an eponymous solo exhibition at the Open Graphic Art Studio in Skopje. She exhibited the photo and video documentation of the performance and an accumulative installation of one ton of salt.

iv Sigmund Freud “A Note Upon the ‘Mystic Writing-Pad” (1925)., The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Ed. James Strachey. Volume XIX (1923-1925): The Ego and the Id and Other Works, London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1978, 225-232.

v For example during the first project Small Lake the artist had intervened on zinc plates with found objects – stones, branches, grass - from the lake, or the second project I and the Eye included hand-writing on the snow.

vi Back in 1996 Čapovska similarly brought sand from the Australian’s dessert Kakadu to the Small Lake and mixed it with the lake’s own soil.

vii Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton, London: Continuum, 2001, p. 374.

viii Ibid., p. 374.

ix Ibid., pp. 374-275.

x Gilles Deleuze Nietzsche and Philosophy, trans. Hugh Tomlinson, London: Athlone Press, 1983, p. 46.

xi Deleuze, Difference, pp. 372–274.

xii Miguel Cañedo-Argüelles, Ben Kefford and Ralf Schäfer, “Salt in freshwaters: causes, effects and prospects” - introduction to the theme issue 03 December 2018, The Royal Society Publishing, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rstb.2018.0002.

xiii Martin Savransky and Isabelle Stengers, “Relearning the Art of Paying Attention: A Conversation.” SubStance, Volume 47, Number 1, 2018 (Issue 145), pp. 130-145.

xiv See: Virginie Maris, Ecofeminism Towards a fruitful dialogue between feminism and ecology, Eurozine, 30 October 2009 https://www.eurozine.com/ecofeminism/

xv Michael E. Zimmerman, J. Baird Callicott, George Sessions, Karen J. Warren, and John Clark (Eds.), Environmental Philosophy: From Animal Rights to Radical Ecology. Englewood Cliffs (NJ:Prentice-Hall, 1993), p. 253.

xvi Mary Daly, GYN/ECOLOGY The Metaethics of Radical Feminism (Beacon Press: Boston, 1978, or Ecofeminism, Women, Animals, Nature, Ed. by Greta Gaard (Philadelphia, PA.: Temple University Press, 1993).